The original Spice Islands were the Moluccas, those remote isles of cloves and nutmeg that lie some fifteen hundred miles east of Djakarta, Indonesia. But throughout history, the location of the Spice Islands gradually broadened to include all of the East Indies — now the countries of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore. There was a simple reason for the wider definition: the spice-growing locations expanded as the region was conquered by one spice-seeking world power after another.

Photo by Marta Branco from Pexels

But about A.D. 100, the Romans built ships large enough to sail to India and back, a trip that took roughly a year. Soon the Arab spice monopoly was broken and prices dropped. The Romans enjoyed only a slight break in prices, since the Indian merchants still wanted a good profit. But because of the increased availability of spices the Romans proceeded to spice their wines, write spice cookbooks, and bathe in spiced oils. However, the fall of the Roman empire (which cannot be blamed on spices alone!) ended such trade, and the Arabs gradually regained control of the spice routes from India.

While that was happening, the Indians themselves took quite an interest in the Spice Islands. Around the fifth century A.D.(some sources say as early as the eighth century B.C.), both Buddhist and Hindu traders arrived in what are now Malaysia and Indonesia, bringing spices like cumin and coriander and vegetables such as mangoes, eggplants, and onions. They were the first outside culinary influence on the region, but their primary interest was money, not cooking.

The Indians set up trading posts, which became city-states, each ruled by a local Malay chief who favored the interests of the Indian traders. These posts were midway between India and China, and they serviced the Indian traders plying the seas between the two great civilizations. By the ninth century, Indian traders, operating from the island of Java, held the first spice monopoly in the region.

But the Arabs were not far behind. The spread of Islam, combined with the continuing interest in spices, led Arab traders directly to the source — the Spice Islands. By the eleventh century, they had literally taken over the spice trade from the Indians, and Hinduism had been replaced by Islam as Muslim seafarers began colonizing many of the Indonesian Islands. The Arabs had barely won control of the spice monopoly when competition came from another source — Europe.

Marco Polo was the first westerner to visit the Spice Islands, landing in Sumatra around 1292. It is said that he was the one who named the region the Spice Islands, because he found black pepper, nutmeg, and cloves growing there. Other spices are native to the region as well, including cinnamon, cassia, turmeric, and ginger, although some sources claim that ginger is native to India and was brought to the Spice Islands by the early Indian

traders.

The European desire to take advantage of the region was delayed, however, by the daunting distances, and the Arabs controlled the spice trade until the late fifteenth century. They shipped the highly valued spices from the Spice Islands to Alexandria, Egypt, and from there Venetian ships carried them to Europe. The spices were so valuable that black pepper was used to pay taxes in England, and European female slaves were traded for cinnamon and cloves. In Germany, a pound of nutmeg could purchase seven oxen.

But Vasco da Gama’s circumnavigation of Africa in 1497—99 changed the spice trade forever. After landing at Calicut, India, he soon learned that although the Indian traders would not sign a formal treaty with the king of Portugal, they would gladly sell the Portuguese all the spices they wanted — in return for gold and silver. The Portuguese moved quickly to end the Arab and Venetian monopolies through both trade and war.

Lisbon soon became the new spice capital of Europe, eclipsing Venice completely. As the Portuguese historian Tome Pires notes, “Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat port on the west coast of Malaya.) Portuguese warships attacked Muslim ports in India and Ceylon, thereby successfully interrupting the Arab spice trade. In 1509, the combined Arab fleet from Egypt and Calicut was defeated by Francisco de Almeida off Diu, in western India. It was one of the most important naval battles in history, and soon the Portuguese expanded their raids to the Spice Islands themselves.

After the Portuguese conquered Malacca in 1511, they expanded their territory to include parts of what is now Indonesia. Portuguese and Spanish traders introduced beans, chiles, tomatoes, corn, and potatoes to the region. The Portuguese also introduced the peanut, via Africa, and it became one of the dominant tastes in Indonesian cookery.

The Portuguese controlled the Spice Islands for about seventy years, until they came under attack by Dutch forces. The Dutch forced a Portuguese retreat to the city of Ambon in 1580, decisively defeated the Portuguese fleet, and captured Java in 1602. They finally captured Malacca in 1641, effectively removing the Portuguese from the region.

The Dutch formed the Dutch East India Company in 1602 to control the spice trade. The company announced that the entire region was to be known as the Netherlands East Indies. The Dutch introduced cauliflower, cabbage, and turnips and worked hard to maintain their monopoly of the spice trade, putting into action the supply-and-demand theory. By cutting down three quarters of the spice trees in the Moluccas, including the valuable cloves, they reduced supplies, raised spice prices, and did not have to defend the Moluccas. They imposed the death penalty on anyone who possessed or sold nutmeg and cloves illegally. The domination of the spice market by the Dutch so upset the British that they founded the East India Company in India in order to compete in the spice trade; however, the Dutch managed to control the Spice Islands (with the exception of a brief period of British rule from 1811 to 1816) until they were occupied by the Japanese, in 1942.

Today, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia are separate, independent countries, and these “spice islands” still live up to their name. Indonesia produces about 70 percent of the world’s nutmeg and mace, plus large amounts of cassia, turmeric, black pepper, and cloves. Most of the cloves consumed in Indonesia, incidentally, are not eaten but rather are smoked in cigarettes.

Other curry ingredients grown in the region include chile, ginger, galangal, lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, and coconut, the last perhaps the most important single ingredient in Spice Island curries. These culinary components, combined with the many ethnic influences on the area, have created a fascinating and complex gastronomic stew.

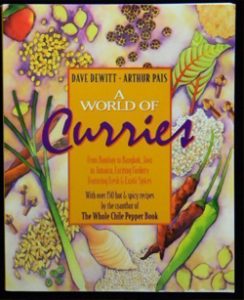

Editor’s Note: This piece is just a fraction of the information and recipes you’ll find in Dave DeWitt’s A World of Curries, available here.

The following two tabs change content below.

Managing Editor | Mark is a freelance journalist based out of Los Angeles. He’s our Do-It-Yourself specialist, and happily agrees to try pretty much every twisted project we come up with.

Latest posts by Mark Masker (see all)

- 2024 Scovie Awards Call for Entries - 07/07/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Special: 3 Days Left - 06/29/2023

- 2024 Scovie Awards Early Bird Deadline Looms - 06/25/2023